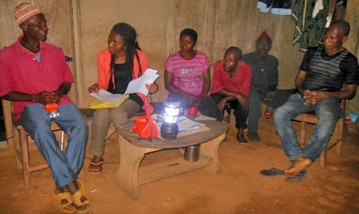

Around the Takamanda National Park, hunting has been a way of life for as long as the people can remember. They have fed their families and created traditions and belief systems based on the wildlife around them. In November 2014, EGI carried out focus group discussions to find out more about the beliefs, knowledge, attitudes and expectations and practice of villagers towards wildlife management in Takamanda National Park. Discussions were held with hunters, bush meat traders, local leaders such as chiefs and members of Village and Forest Management Committees (VFMC) in nine villages that share a boundary with the Takamanda National Park (Kajifu 1 and 2, Kekukesim, Takamanda, Obonyi 3, Obonyi 1, Assam, Okpambe and Takpe).

The findings of this exercise highlight a marked positive attitude and effort to contribute to conservation efforts.

Main drivers of hunting and bush meat trade

Poverty and the requirements to cater for household needs, coupled with the lack of education (and therefore skills) to undertake other forms of gainful employment are cited as the main reasons for hunting and bush meat trade. This is further driven by a ready market and rising prices for fresh and dried bush meat. Whereas many people hunt only for household consumption, commercially oriented hunters choose the species to hunt based on market demand. Most respondents hunt birds only as a last resort, in case they do not catch other animals, and usually mainly for consumption as food.

Deterrents to hunting

There is a general observation that sightings of certain animal species e.g. giant pangolin, water buffalo, drills, elephants and gorilla have become rare as a result of hunting and other human activities like logging. “I have heard from others that the animals have crossed to the national park in Nigeria. I believe if this hunting can reduce, then some of them may come back to our forest,” says Ojong Stephen from Kajifu 2. Migration of animals has reduced chances of making a catch, forcing many to adopt other activities, especially farming.

The wellbeing of the younger generation serves as an influencing factor for some respondents to reduce hunting. “It’s important to stop hunting because some of these animals are not known by our children and I believe the best method of teaching children is by showing them the animals physically,” says Olakwa George, from Takamanda village.

The recognition of, and personal experience of dangerous encounters with wild animals is also cited as a deterrence to hunting. This is the case of 68-year old Ashu Emmanuel. He says, “What happened was that I had left my farm and decided to go and hunt for some meat for my family. I came across about 60 bush pigs. I aimed and shot at a female one, and before I knew it, a male one came charging at me. I fought it off, and in the process it bit off my finger.” Ashu knows how lucky he was, and even though it has been 18 years since that incident occurred, he has never gone hunting again. In fact, his entire family is forbidden from hunting.

There were times that indiscriminate hunting went on, out of lack of awareness about the impact on wildlife, and also lack of understanding of wildlife laws. Efforts made by wildlife enforcement officers and civil society organizations in the area seem to be making an improvement. Some respondents ceased hunting activities after they were informed about the law, either through seminars and workshops, or through awareness activities undertaken by VFMC members.

Economic activities considered viable alternatives to hunting

Farming is the most commonly cited as an alternative to hunting, and also as a primary source of income for most respondents. Food crops cultivated include cassava, plantains, banana, maize, bush mango and egusi. This economic activity is increasingly attractive because of the guarantee of regular income, and the opportunity to cultivate cash crops, such as cocoa and oil palm. Some respondents have reduced hunting not only because of the enforcement of conservation laws, but also because of the time-intensive nature of farming, which leaves them little time to go hunting.

Even though some of the respondents admit that it will be difficult to completely stop hunting for food at present, they see fishing and raring of goats, hens and pigs as potential replacements.

Existence of local environmental governance structures

VFMCs are established as part of local governance structures to ensure that the rules and regulations that have been agreed upon with regard to accessing and using forest resources are adhered to. They patrol the forests, participate in meetings and render reports to the government officials responsible for forest and wildlife management. Specifically, both VFMCs and community members highlight that slash and burn clearing, use of chemicals for fishing and clearing of farms are prohibited, and there are specific guidelines on the timing and conduct for collection of non-timber forest products.

Chiefs, VFMC members and other community leaders have had opportunities to attend seminars, and workshops organized by Takamanda National Park management, and to attend national fora on wildlife management. At the level of community members, there is a general understanding about blanket restrictions, penalties and bonuses.

Traditional societies like Egpe and Ekwe also play a role in promotion of conservation practices. For example, the Makwo law has provisions for punishing those who carry out harmful practices within the forest. These traditional systems play an important role in preventing unsustainable use of natural resources such as water, forests and wildlife.

The focus group discussions in the nine villages highlighted the strong leaning and acceptance of the legal aspects of conservation and natural resource management. Therefore, stepping up efforts to educate communities about environmental laws, policies and regulations, will enable them to take informed action that will contribute to sustainability goals related to the environment.

More importantly, more work needs to go into understanding the traditional knowledge and systems, beliefs and attitudes towards natural resources. These aspects will help those involved in wildlife management to design programs that adequately address human behaviour and the motives and motivation behind such behaviour; and which create adequate space for public involvement. It will also provide the background required to develop effective community education programs and to create persuasive messages which will influence behaviour change.